6 min read

In life, we are always carrying some level of stress, so our tendency to take on more than we can handle often feels manageable. Until it doesn’t.

We mistake “numbness” for “stamina,” which is why taking on more rarely feels like too much at first.

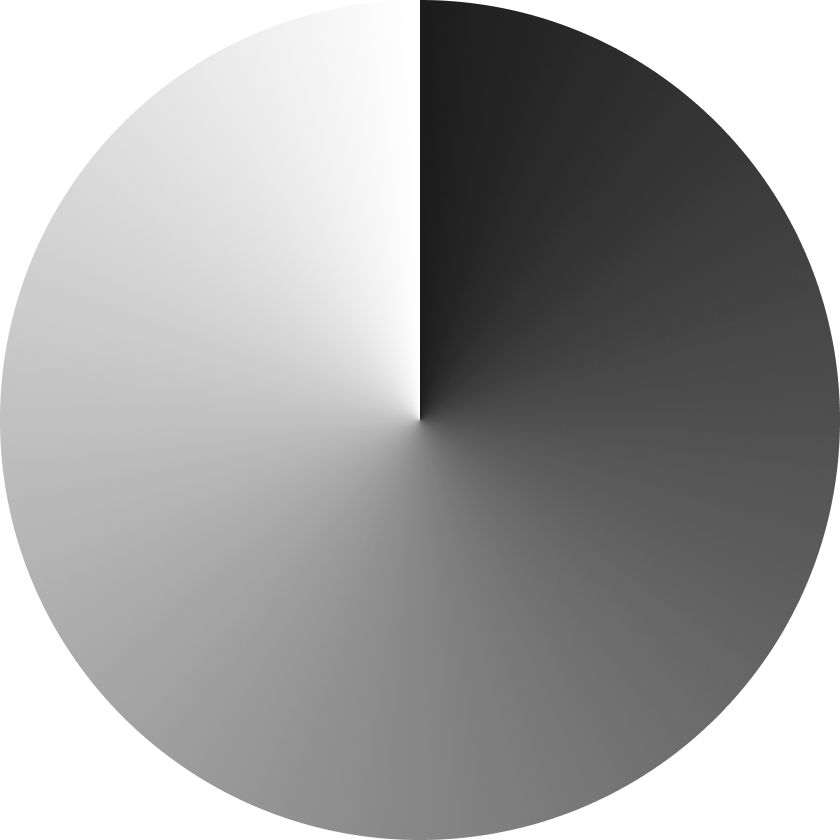

But stress isn’t linear; the closer we get to our threshold, the more rapidly the intensity spikes and by then, it is often too late to dial it back.

I saw that pattern clearly one Tuesday morning.

My first training client of the day walked into the gym visibly stressed.

Our normal rhythm is easy going. We do our usual check-in and talk about sleep, nutrition, work, life, then move right into the session. But that morning, the conversation stayed short.

As a trainer, a big part of the job is learning how to read the client and the room before any work is done. That skill matters because training stress doesn’t start and stop with the session itself.

What someone can handle on a given day depends on their current mental capacity for stress, how much rest they’ve had, and what they’ve already been carrying emotionally before they ever touch a weight.

When those pieces are misaligned, even solid programming can push someone toward overreaching rather than adapting to their current state. Being able to recognize that moment and adjust while still honoring the intent of the session is where good programming turns into great coaching. It’s also what keeps progress moving forward while reducing the risk of overtraining and injury.

A lot of the real work in coaching happens before the first set ever starts, and it’s easy to miss if you’re only looking for movement and numbers.

During the ten-minute warmup, her focus drifted. There was a subtle irritability under the surface. She didn’t want to slow down and didn’t want to prepare, so that’s when I decided to pivot my plan and let her effort do the talking instead, knowing it would either settle her or expose something.

I structured the session to start with a 15-minute AMRAP (As Many Rounds As Possible.) You stop when you need to, and you decide when to start again. The goal is to keep moving, but pacing is everything. Push too hard too early and the workout will expose inefficiencies.

The timer started.

She came out strong, focused and aggressive, but as she went through the exercises she refused to take breaks.

After the first round, her pace slowed dramatically. I reminded her that rest was available whenever she needed it. That she was in control of that choice.

She acknowledged it, briefly considered it, but kept moving. Her eyes stayed locked on the timer and fatigue was starting to set in.

By the end of the second round, she couldn’t sustain the intensity. Her breathing shortened and her form started to slip. She was pushing herself, but the effort was no longer productive.

I stopped the clock early before starting the third round.

As she caught her breath, I checked in. ‘Are you okay, How are you feeling?’

Eyes closed, she stood there trying not to throw up. If she wasn’t aware of her state before, she was now.

In the first round, she gave everything she had, but she overestimated how much she could sustain all at once.

You can’t outwork stress.

What showed up in that moment wasn’t a lack of effort on her part. It was the cost of ignoring signals.

For my client, life stressors had been stacking up, gradually compromising her resilience and pulling her attention away from her own well-being.

We tend to stop only when the body forces us to. Fatigue has a way of humbling the part of us that believes we can push through anything. And this isn’t limited to training.

The same thing happens in life. We take on more work. We sacrifice personal time.

We delay rest because it feels inconvenient or undeserved, but stress keeps track anyway. Physical, mental, emotional, physiological. It all counts.

Collectively, it seems we can’t stress enough.

AMRAPs frame this clearly. Rest is technically available, but it isn’t always accessible in practice. It requires awareness and restraint. Without those, rest becomes reactive instead of intentional.

We often outsource this awareness. We wait for the end of something, or for someone, to tell us when to slow down and even then we ignore the suggestion. We build lives where things like recovery, breaks, and rest feel like something that happens later, outside of our waking hours. Until failure becomes the only interrupt.

That morning, training stripped away my client’s usual hiding places for performance.

What remained was a clearer picture of not just her physical strength, but her mental efficiency. She lacked the ability to pace herself, to notice her own redline, and to choose when effort needed the counterbalance of a break.

She began to recognize, perhaps for the first time, the need to slow down and take inventory of what was actually within her control. The body has a way of signaling everything we need to notice, long before things break. And that kind of awareness is harder to train than strength. It matters far more than most people realize.